Scope 4: Degradation

The hidden emissions we don’t count: how net-zero accounting is driving the slow erosion of quality, durability and trust.

Welcome back to The Ledger - a weekly briefing of what’s happening inside complex systems around industrial decarbonisation. Welcome to Issue #12.

Your chocolate has less cocoa because cocoa’s carbon footprint is too high for the spreadsheet. Your paint covers poorly because titanium dioxide is “energy intensive.” The quiet revolution isn’t electrification - it’s reformulation.

THE OPENING ENTRY

A consumer goods giant’s sustainability meeting, London. The carbon consultant is explaining their roadmap to net-zero.

“Cocoa: 17kg CO₂ per kg. Palm oil: 3kg. The substitution alone gets us 15% toward our Scope 3 target.”

The procurement director nods. “And it saves £8,200 per tonne.”

“That’s... a coincidence,” says the consultant.

Everyone pretends to believe her.

This is the untold story of industrial decarbonisation. Not the shiny heat pumps or hydrogen trials. The real action is in reformulation - swapping high-carbon ingredients for low-carbon alternatives that happen to be cheaper.

Products are worse, but the carbon numbers have never looked better.

THE ACCOUNTING PHYSICS

This isn’t corporate malice. It’s accounting physics.

In carbon disclosure, emissions count where they’re produced, not where they’re caused. The closer you are to the consumer, the more you can outsource your footprint upstream. Reformulation is simply arbitrage.

These teams aren’t villains. They’re trapped between investors demanding decarbonisation and consumers unwilling to pay for it. When the spreadsheet decides, cocoa loses to palm.

FIELD REPORTS

1. The Carbon-Optimised Chocolate

Major confectionery plant, Birmingham. They’ve replaced 40% of cocoa butter with palm-based CBE (Cocoa Butter Equivalent). Not for cost - officially. For carbon.

“Cocoa farming in West Africa: 5.7 tonnes CO₂ per tonne of butter. Palm oil from Malaysia: 0.8 tonnes. It’s a climate win,” the sustainability manager insists.

The reality? Cocoa prices hit £9,600 per tonne. Palm alternatives cost £1,200. But you can’t tell investors you’re cheapening products. You can tell them you’re saving the planet.

The new chocolate melts at 38°C instead of 34°C. Doesn’t matter for carbon accounting. Matters quite a bit in your mouth.

“We’ll hit our Science Based Target,” she says. “The chocolate tastes different? That’s consumer adaptation to climate necessity.”

The same pattern holds in another sector - different product, same substitution logic.

2. The Low-Carbon Paint

Coatings manufacturer, Newcastle. Titanium dioxide (the white pigment) requires 2,100°C processing. At UK industrial electricity prices - four times US rates - and with carbon taxes looming, it’s unsustainable.

Solution? Replace with calcium carbonate. Needs only 900°C. Carbon footprint drops 70%.

The sustainability report celebrates: “40% reduction in process emissions achieved!”

The technical datasheet, buried deep: coverage reduced from 13m²/litre to 9m²/litre.

Customers now need 44% more paint for the same job. The carbon savings? Eliminated by extra production, transport, and packaging. But that’s Scope 3 - someone else’s problem.

“We measure what we manufacture, not what customers use,” the technical director explains.

In food manufacturing, the reformulation play is even more visible - because we can taste it.

3. The Plant-Based Pivot

Meat processor, Yorkshire. Sausages went from 72% pork to 51%. The official reason: “Responding to climate-conscious consumers with reduced-meat options.”

The real driver? Their carbon tax exposure. Pork: 7.6kg CO₂/kg. Rusk and potato starch: 0.9kg CO₂/kg.

Plus, with UK energy costs crippling manufacturing, lower meat content means 40% less cooking energy. They’ve cut gas consumption by 1.2 million kWh annually.

“It’s a transition product,” marketing claims. “Helping consumers reduce meat gradually.”

The CFO is blunter: “Carbon taxes would have killed our margins. This keeps us competitive until lab meat arrives.”

Quality? “Different consumer expectations for climate-friendly products,” he says.

Sometimes the carbon maths produces genuinely surreal outcomes.

4. The Petrochemical Paradox

Chemical company, Teesside. Their entire personal care range reformulated to hit Scope 3 targets. Natural oils (high carbon) replaced with petrochemical derivatives (lower carbon, paradoxically).

Why are fossil-based ingredients “greener”? Because they’re already extracted for fuel. The carbon accounting assigns that emission elsewhere.

“Virgin coconut oil: 2.4kg CO₂/kg. Synthetic alternative from refinery by-products: 0.3kg. The maths is clear,” says their carbon accountant.

Clear for carbon. Less clear for the scalp irritation reports up 300%.

“Consumers must adapt to sustainable chemistry,” insists the head of sustainability. The dermatology complaints are filed under “transition challenges.”

And in commodities, efficiency has become another word for thinness.

5. The Efficiency Extraction

Paper mill, Wales. Tissue products now 40% lighter GSM. Official position: “Optimising fibre use for forest sustainability.”

Actual position: UK energy-intensive industries’ output has fallen by one-third since 2021. At the lowest level since 1990. Every gram of pulp not processed saves energy they can’t afford.

They’ve installed a carbon dashboard in reception. Shows 45% reduction in manufacturing emissions.

Doesn’t show customers using 60% more product to achieve the same result.

“We manufacture sustainable tissue,” the CEO says proudly. “Usage patterns are consumer choice.”

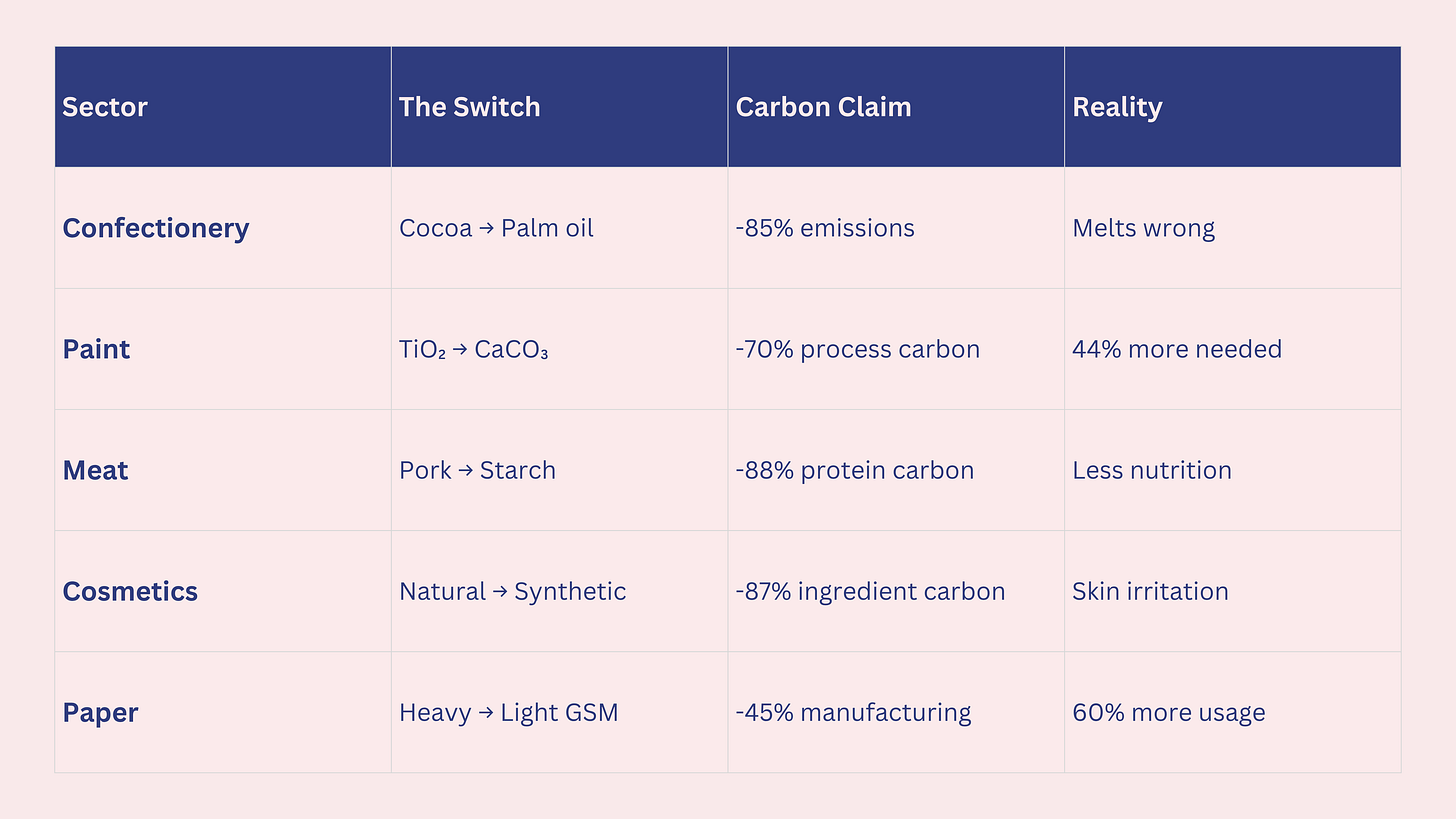

THE CARBON COMPROMISE INDEX

The pattern is systematic:

WHAT THE LEDGER REVEALS

The decarbonisation of industry is real. The numbers are improving. Targets are being hit.

But dig deeper:

“Low-carbon” ingredients are often just cheap ingredients rebranded

Process emissions drop by making products that need replacing sooner

Scope 3 targets make carbon someone else’s problem

Carbon accounting rewards degradation as “efficiency”

62% of manufacturers admitted reformulating for costs. But now they call it “sustainable innovation.”

The carbon consultant who started this story told me privately: “Every sustainability target is met by either genuine innovation at 10x the cost, or reformulation at half the cost. Guess which companies choose?”

THE CARBON ACCOUNTING GAME

Here’s how it works:

Your carbon footprint: Measured at factory gate

Their carbon footprint: Not your problem

Make chocolate that melts wrong? Consumer storage emissions (not yours).

Paint that needs three coats? Consumer application emissions (not yours).

Products that fail early? Consumer replacement emissions (not yours).

The system incentivises exactly what we’re seeing: products that hit carbon targets by becoming worse.

One sustainability director admitted: “We could make products that last twice as long with 20% more embedded carbon. But that would blow our targets. So we make products that fail faster with lower manufacturing emissions.”

THE GREEN PREMIUM INVERSE

Economics assumed green products would cost more - the “green premium.”

Reality: With UK electricity prices 46% above global average and carbon taxes rising, genuine quality is becoming the premium.

The “green” version is now often the degraded version:

“Climate-friendly chocolate” = less cocoa

“Low-carbon paint” = worse coverage

“Sustainable sausages” = more filler

“Eco-conscious cosmetics” = synthetic substitutes

The green transition is happening through quality erosion disguised as environmental progress.

THE OPERATOR’S REALITY CHECK

For manufacturers:

Stop pretending reformulation for cost is reformulation for carbon

Measure whole-life carbon, not just manufacturing

One durable product beats three “low-carbon” disposables

Admit when green and good diverge

For policymakers:

Until carbon accounting measures total lifecycle performance, we’ll keep mistaking degraded quality for environmental progress

For everyone:

“Carbon neutral” often means “neutrally terrible”

Check if “sustainable” just means “sustained degradation”

Real environmental progress doesn’t require worse products

Quality that lasts is the ultimate low carbon

THE LEDGER LINE

We’re achieving net-zero by hollowing out the very things we used to value: quality, durability, taste.

The world’s decarbonising - one compromised product at a time.

The carbon compromise isn’t between economy and ecology. It’s between appearing green and being good.

And until we change how we count carbon, we’ll keep celebrating the systematic degradation of everything we make.

Thanks for reading, and please share The Ledger if you have found it useful or insightful in any way.

Here’s to what’s possible

Dom